Contents

Big Sheets is my attempt to build a software using concepts of clean architecture, hexagonal architecture, Domain Driven Design (DDD), and a bit of event-driven programming; by following the amazing book Architecture Patterns with Python.

This post introduces the architecture of the software, so you can take a peek at the code after, and comments a few challenges and learnings from the experience. If you are a practitioner, Big Sheets can serve you as an elaborated example.

Introduction

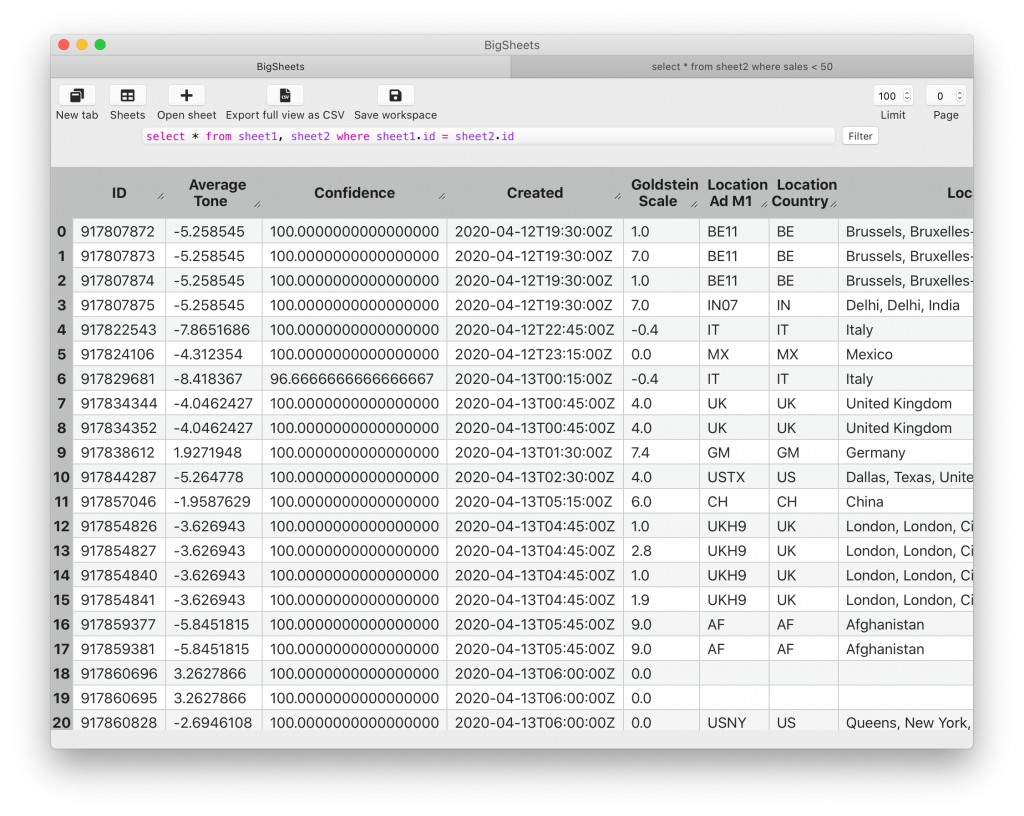

Big Sheets —sad pun intended— is a convenience desktop software to analyze CSV files (sheets) by querying them using SQL. Opening CSVs translates to creating tables in a database —so you can join, aggregate them, etc. Excel meets SQL, replacing those nasty excel functions (that I am not bothering to learn) for comforting SQL statements. The software is at GitHub, where you have installation instructions.

The software is a desktop software, as I wanted to go as far as I could from my expertise and the example the book Architecture Patterns in Python (from now on, the book) uses: a web service.

Note that this is an unfinished project and by writing this I am looking for reviews to improve it. Moreover, I don’t pretend perfect code, but a good architecture. So, judge everything you see, don’t be surprised if I change anything, and please comment on the first smelly thing.

I assume that you, the reader, has some knowledge about clean and/or hexagonal architecture, Domain Driven Design, and event-driven programming. Otherwise, I recommend checking the following links, which I cite through the post:

- An introduction to hexagonal architecture, by the creator itself.

- An introduction to clean architecture, by the creator itself.

- An article that joins the different architecture and patterns in one diagram and explanation.

- The book, which I followed to build this project.

- And of course, the repository of the project, so you can have it in a side window while reading this.

And finally, this table can help you in unifying terminology:

| Cosmic python project structure | Hexagonal architecture | Clean architecture | |

| 1 | Entrypoint | Primary adapter on a port. Driver. Primary actor. The trigger of the use case. | Boundary. For example, a presenter. |

| 2 | Adapter | Secondary adapter on a port. Driven. Secondary actor. It is called through the use case. | Boundary. For example, an entity gateway. |

Without more preamble, let’s go!

The use cases

The following are the main use cases of the app. Although they are self explanatory, their description is in the test_use_cases file, so the use case contracts and tests are at the same place.

- Open a CSV sheet when opening the app.

- Open another CSV sheet once the app is opened, so we can have multiple sheets opened in the same running app.

- Query a sheet, using the SQL.

- Save the workspace, meaning saving all the opened sheets, windows, and queries.

- Load the workspace, so we can restore the workspace.

- Export a view, saving in a CSV the result of querying with SQL.

- Close a sheet.

- Close a window.

- Close the app.

The architecture

The following diagram represents the architecture of Big Sheets.

- The main domain are sheets themselves —recipients of the use cases.

- The BigSheets app is the first piece that is executed when the user opens the app, and it bootstraps the whole system.

- As an event-driven system, events and Commands are the main way to trigger use cases. Commands represent the use cases above, and events are triggered when those commands are finished.

- The GUI adapter manages the windows, the presentation of the sheets, and it is where the user interfaces with the system.

- The sheets adapter is the responsible to load and save them into files and SQLite databases.

- The Read Model is a Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) implementation that the GUI can directly access to simplify and speed-up retrieving sheet information.

- As unfortunately CSVs are very free-form, we have a dedicated model and adapter to manage errors when dealing with CSVs.

- The message bus is a poorman’s way of achieving an event-driven system, with commands. If you want to replicate a similar exercise, the implementation can be useful.

As a hexagonal architecture

We can diagram the system using the hexagon of the hexagonal architecture.

Project structure

The following is a noise-free version of the project structure. I am following an adapted version of Architecture Patterns with Python (Appendix B):

├── Makefile

├── README.rst

├── bigsheets ❶

│ ├── adapters

│ │ ├── container.py

│ │ ├── error

│ │ │ └── error.py

│ │ ├── sheets

│ │ │ ├── file.py

│ │ │ └── sheets.py

│ │ └── ui ❷

│ │ ├── gui

│ │ │ ├── gui.py

│ │ │ ├── query

│ │ │ │ ├── controller.py

│ │ │ │ ├── query_window.py

│ │ │ │ └── view.py

│ │ │ ├── utils.py

│ │ │ ├── warnings

│ │ │ │ ├── view.py

│ │ │ │ └── warnings_window.py

│ │ │ └── web-files (html files)

│ │ └── ui_port.py

│ ├── app.py ❸

│ ├── domain

│ │ ├── command.py

│ │ ├── error.py

│ │ ├── event.py

│ │ └── sheet.py

│ ├── main.py ❹

│ └── service

│ ├── command_handlers.py

│ ├── event_handlers.py

│ ├── handler.py

│ ├── message_bus.py

│ ├── read_model.py

│ ├── running.py

│ ├── unit_of_work.py

│ └── utils.py

├── requirements.txt

├── setup.cfg

├── setup.py

└── test

├── conftest.py

├── e2e

│ ├── README.rst

│ └── test_use_cases.py

├── fixtures

├── integration

│ ├── backup.sqlite

│ ├── package-lock.json

│ ├── test_handlers.py

│ ├── test_read_model.py

│ └── test_sheets.py

└── unit

├── test_container.py

├── test_message_bus.py

└── test_unit_of_work.py

❶ The bigsheets folder is divided into adapters, domain, and service. If Bigsheets became bigger, we would probably divide this folder (and its adapters, domain, and service) by logical components —context boundaries, aggregates, etc.

❷ The UI is a port (as an interface) that has a GUI class that implements it. Differing with the book, this is not in an entrypoint folder but as an adapter, as I consider it both a driver and a driven adapter.

❸ & ❹ The files that bootstrap the app.

A challenge: notifying updates of a progress

There is an interesting exception of the event-driven programming in the system; updating the progress of a long-running operation. For example, the app fills a progress bar when new rows are read from the file and stored in the database.

In the book, we generate events when finishing an operation. In BigSheets, an example is SheetOpened. Once a sheet is opened, the Unit of Work (like the book) emits the event, and the GUI receives it and updates itself.

But how do we notify the GUI about a sheet half opened? We can emit an event SheetHalfOpened. If the Unit Of Work emits it, it breaks the unit of work itself, so we should explore other options (the book names a few), adding to the implementation. Moreover, receivers of SheetOpened are assured that the sheet has opened, otherwise there is no event at all, but with a SheetHalfOpened we would need a SheetDidNotOpen to notify failure. And finally, there is the performance problem of executing the message bus machinery every few seconds to just update a progress bar.

So, in this case I ended up breaking the event design and access directly the GUI from the handler. An experienced event-driven programmer could propose a better solution.

As a side note, I had another challenge: the update came from the sheets adapter (which is opening the file), and it has to end-up in the GUI without coupling them.

Conclusion

The trigger to learn these architectures and patterns was the tightly coupled softwares I was working on (the big wall of mud), and the accompanying frustration of investing so much time in patching and adapting code —chores— instead of adding new functionality.

Which is exactly what this architecture solves. Adding and changing functionality is faster and less messier, minimizing cruft. The following sub-section, Isolate it, is an example.

However, applying these architecture and patterns is not going to be always possible, nor desirable —for example if building a prototype or a CRUD application. The initial time to market is greater and the performance hit is there.

Martin Fowler explains it from another point of view.

There are two learnings, not totally inside the scope of the architecture, that I think I can carry in every project, and maybe they are helpful, or obvious, to you. In the end, this has not only been only about learning a new architecture, but a way of reasoning when translating problems into code.

Isolate it

Separation, encapsulation, boundaries, decoupling; are kings. And I have two main reasons for it:

Firstly, by learning how to build desktop apps and applying the architecture, I changed libraries and code. As my free time is scarce, many parts are still spaghetti-code (*whispers* like a real project). I totally re-did the message bus (it was async!). If I can do and re-do at pleasure is because there is no coupling with other parts of the system.

Secondly, is testing. As a Test Driven Development (TDD) follower, this was not a new concept for me, but following an architecture that rigorously sets boundaries really simplifies and speeds up testing. Implementations now are ridiculously easy to swap with mocks.

If I had to create a project in a rush, which I know it would substantially grow, the only thing I would try to do is following this separation —the rest, at the beginning, could be ugly intern code. And I would rest well at night knowing that future modifications would have controlled effects. Similar knowledge is in the book.

You command the framework, not otherwise

Robert C. Martin describes it the following way in the Screaming Architecture:

So what does the architecture of your application scream? When you look at the top level directory structure, and the source files in the highest level package; do they scream: Health Care System, or Accounting System, or Inventory Management System? Or do they scream: Rails, or Spring/Hibernate, or ASP?

When running an app, like a Flask, React, or Django one, the first lines of the main.py or index.js usually bootstrap the framework and, then, the framework loads your views, database, etc. —the framework bootstraps and commands your app. You are chained to its boundaries. Extensions, like Flask-SQLAlchemy, worsens this by chaining your app even more.

With Bigsheets, the app.py has a class BigSheets that bootstraps the app. The start method, called after bootstrapping, initiates the UI —but it could initiate a Flask instance, or a CLI, or all of them. It is a statement; your app now controls the framework.

Breaking this mental chains eases thinking out-of-the-box, out-of-the-framework boundaries.

Next steps

Any reader that looked at the code would see there is big room for improvement. The following is an incomplete list of what I would like to keep working on (in case you want to share some knowledge or contribute):

The domain model is anemic: service commands are doing the heavy-lifting, and adaptors like sheets could offload some code to them domain. Business rules are mixed with user interactions as the app is the business itself, so it is hard to adequately separate them.

This app only has one bounded context, which the aggregate root is Sheets. Adding another one would provide a learning experience —ex. adding a shared kernel and divide the project structure by layers, too.

Adding a CLI, alongside with the GUI, would be an exercise in evaluating code decoupleness, learning pains, benefits, and effects.

Completing the tests, specially the descriptions, which I am doing with Gherkin —as I want the use case documentation as close as possible to the tests.

And if the app is ultimately useful to someone (it is with me and my big CSV files), we can always add new functionality. Personalizing the CSV parsing or making it work in GNU-Linux / Windows could be good starting points.

Happy coding 🙂